Biography

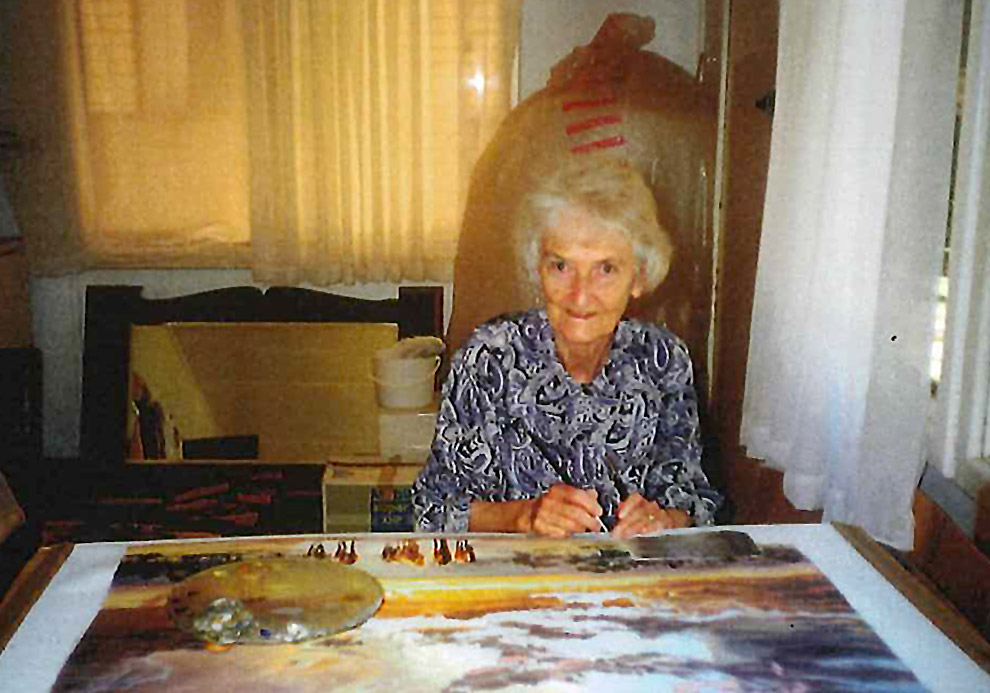

Ailsa Small (1931-2014)

The unique clarity and depth with which Ailsa Small endows her work is a legacy of her father. Peter Small was born in Scotland, and inherited an enthusiasm for art from his father which has its roots in centuries of European representational painting. He loved the work of the masters as diverse in time and theme as Michaelangelo and Constable, but held Rembrandt in special regard, “because he did faces beautifully”, Ailsa says. He took art lessons at college, and while at university studying to be a solicitor, continued with private lessons. Among his tutors was his uncle, Robert Small, a member of the British Royal Academy. But Peter Small was never to make a full career from his training in either law or art. World War One intervened. After surviving the conflict, during which he rose to the rank of captain with the Gordon Highlanders, he was unable to settle down. He initially made plans to travel to Canada, but then in 1920 joined friends on a ship to Australia. His first job after his arrival in WA was on a farm, where he met his future wife, Annie Mather. After several years with a surveying team, and an abortive attempt to farm at Grass Patch, Peter and Annie took up land 40 kilometres east of Mullewa, and the name they carved from it ‘Challymenda’. Here they raised four daughters, of which Ailsa, born in 1931, was the second.

Long hours on the farm meant Peter Small was only able to pursue his painting during the wet weather. However, he passed on his skill and love of art to his daughters, all of whom are accomplished artists. Ailsa cannot remember when she began to draw, it was an instinct that was always there. Her earliest memories are of taking drawings to her father for advice.

“Dad always encouraged me, and because I admired his work so much, it was easy to follow along.”

Just how quickly she developed her talent under his tutelage was demonstrated recently, when a visiting English cousin showed her a drawing she had done when she was eight. “It was similar to a drawing I would do now. I was surprised.”

Her first work was produced using pencil and pencil crayons,

“Dad only had one box of watercolours. You couldn’t get them easily in Mullewa, they were very precious. I was only 10 when I got my first watercolours. I used them pretty quickly, but my Mum and Dad got me another set, Windsor and Newtons”.

She remembers her main subjects in her early teens were the farm animals, although she was already showing a flair for landscape. A watercolour painted in this period shows sheep walking into a water trough in the low scrub of Challymenda at dusk, with a fiery outback sunset burning in the sky.

Ironically, it was because of her isolation that her talent was brought to the attention of the indefatigable WA art promoter, Claude Hotchin. Hotchin was for many years a member (1947-64) of the board of trustees of the Public Library, Museum and Art Gallery of Western Australia and chairman (1960-64) of the board of the Art Gallery. He was later knighted for his services to art. The Small girls carried out their primary education through correspondence, and Ailsa habitually decorated her papers with small drawings. A correspondence teacher showed the drawings to WA Art Gallery director, Robert Campbell, who encouraged the young artist to exhibit a watercolour in the first Claude Hotchin Art Prize, in 1948. While it did not win, “the fact that it was chosen to hang was encouragement enough.” And Ailsa formed a long friendship with Sir Claude that was to provide her with years of encouragement and useful advice. It was reported that among the dozens of paintings – including Tom Roberts and Will Ashton – that adorned Sir Claude’s house, the place above his bed was reserved for an Ailsa Small picture of pink-and-grey galahs.

Ailsa’s secondary school education was undertaken at Presbyterian Ladies College in Perth. It was here, on her seventeenth birthday, that she was given her first oil paints. “I remember trying them, liking their vibrancy, and thinking, I’ll never go back to watercolours.”

Painting was still a hobby at this time, with Ailsa heeding her father’s advice that she should always paint just for the love of it. However, an opportunity that most young artists only dream of, a scholarship to study overseas, was offered to her. Ailsa refused.

“At that stage overseas they were leaning towards more modernistic styles of painting, and that didn’t appeal. Even here the art establishment was pressuring me to change my style. One person said ‘You will never get on unless you change your style’.”

Determination not to change her style has put Ailsa permanently at odds with an art world trying to encourage acceptance of more modern methods.

Ailsa makes no apologies for her technique.

“To me, the scene is the beautiful thing, not my painting. I have no desire to change a scene – I hope to draw attention to the beauty that is there. I would like to think I was bringing back a piece of it for people to see.”

This was appreciated by critic Ernest Philpot, who reviewed the 1969 Claude Hotchin Art Prize entries, and had this to say about Ailsa’s winning oil; “At first glance it is stodgy, Victorian – the product of a too keen amateurist’s very keen eye. But it has to grip an honest viewer until at last it becomes very lovely in it’s own individual right. It plagiarises nobody. It is simply Ailsa Small in love with her country. The only conclusion one can come to in regard to such a painting is this: If a painter cannot with conviction and integrity plunge into the contemporary world of abstract, the next best thing to do is to translate natural appearances with conviction, integrity and intensity, leading to the apprehension of nature to the degree Ailsa Small apprehends it …There is true ecstasy in this painting.”

Ailsa sold her first painting before she was 20. She had never considered being anything other than an artist, and in this she had the backing of her parents. “I was particularly fortunate that my parents supported me so I could concentrate full-time on my art. Most artists have to take another job.”

While in her twenties and early thirties Ailsa lived at her parents house in Nedlands, developing her skills and earning a living through portrait and commission work, and by sales of original work. And she found a growing passion for landscape painting.

“I’m happiest with landscape. If I’m painting a landscape, and I don’t like it, I can throw it off a cliff – you can’t do that with portraits. Especially as I put so much commitment into portraits. Because I am so detailed, I take longer than most portrait painters, and the subject has to sit longer.”

In 1961 she travelled overseas, to Europe, for the first time. She was able to see first-hand the work of painters who influenced her art. And the trip gave some focus to her work in WA.

“I found I had no desire to paint over there. The light affected me. I don’t often paint dull, soft light, such as they have in Europe, because I’m a bit of a sun-worshipper. I have always lived in bright sunlight. Besides, I felt it had all been painted before, and very well, so I would come back and do my own thing, in my own country and my own state.”

1961 was also the first year Ailsa won the oils section of the Claude Hotchin Art Prize. Sir Claude had provided continual support for the young artist, one of the few figures in the art world prepared to do so. Ailsa had entered every Hotchin Art Prize since 1948 without a win: in the next decade she was to win the oils section four times.

In 1963 Ailsa made a trip that was to have a permanent effect on her painting. On the advice of Ernestine Hill, she and her mother travelled for three months through WA’s Pilbara to the Kimberley, in the State’s far north. Hill travelled north to seek literary inspiration: Ailsa was to find a similar lode for her art. “There is so much beauty there; you can go up for three months and paint it for the next two years.”

This was exactly what she did until her marriage. Two women alone in the Kimberley was a different matter in the 60’s than it is today, and Ailsa recalls their friends “had a blue fit”. But they were more at home in the outback than in the city, and the appalling roads and days of bully beef and damper were made up for by the legendary hospitality of the locals.

The ancient grandeur and brilliant colours of the Kimberley and Pilbara make an ideal subject for a sun-worshipper with an unerring eye. The result, over the years has been a series of canvases which give the viewer a three-dimensional look into one of the most beautiful areas in the world. Such is the splendour of Ailsa’s painting that some who have not been to the region doubt the accuracy of her interpretation. Even the artist has moments of concern.

“I come back from the north and look at the colours and think it must be wrong. But I dare not change it, because I was on the spot when I painted it.”

Others who were not there are not always convinced: “…but I can understand that, because when I was little I remember looking at Albert Namatjira and not comprehending his colours, thinking they were painted stronger than they actually are. It wasn’t until I went there that I knew he had done them exactly right.”

The geology of the Kimberley has also created some disbelief.

“In the first exhibition I had there was a painting named ‘The Battler’. It was of a little old white trunked tree growing right out of the edge of a gorge. There were two old ladies discussing this painting and one said ‘Ridiculous!’ You would never see a tree growing like that. So I knew they had never been there, because that is one of the things you marvel at: trees seemingly growing out of solid rock.”

The exhibition where this took place was held in 1965, at Claude Hotchin’s own art gallery: and the enthusiasm it generated may be gauged from the fact the entire display sold out in the first ten minutes. This success may have something to do with Ailsa’s second win in the Claude Hotchin Art Prize a week earlier. The artist was typically modest about the exhibition, although she supposed the proof of recognition it implied to her at the time, given the lack of support from the art establishment. It was 21 years before she was to hold her next exhibition, but the paintings were still sold out in the first day.

In 1968 Ailsa became Mrs Alfred Flannagan, although she retained her maiden name for painting. The couple had been childhood friends and now, by a striking coincidence, Alf decided to buy Challymenda. The couple have farmed since 1968.

Before her marriage, Sir Claude had advised Ailsa to complete at least two paintings a year, so she could maintain her skills. She did this with such success that she won the Claude Hotchin Art Prize in 1969 and 1970. The last year in which she took the prize coincided with the birth of the couple’s first son, John. Mark followed in 1972.

The next 15 years were mostly filled with the care of her children and the multitude of duties that befall a farmers wife. However, she maintained the at-least-two-paintings-a-year dictum of Sir Claude. Her canvases were also hung at numerous exhibitions including the Redcliffe Art Exhibition of 1967, 1968 and 1971, the Rotary Club of Camberwell (Victoria), in 1974 and 1976, the WA 150th Anniversary board in 1979, the Geraldton Festival Prize, Bunbury Art Award, and the National Heart Foundation Exhibition. In 1986 Ailsa mounted her second sell-out exhibition at the William Curtis Gallery, and in 1989 and 1991 a display at the Bay Gallery of Fine Art met with similar success. Ailsa says she was only able to mount the exhibitions because of the continued support of her mother. Since the early 1980’s Annie Small has taken up much of the household duties at Challymenda, enabling her daughter to devote more time to her art.

Ailsa has made the most of her new freedom. Further trips to the Kimberely and Pilbara have provided her with fresh material, and she has found inspiration closer to home.

Meanwhile, her admirers and those just discovering the vision of Ailsa Small can do so through her website. This shows the broad sweep of the artist – the rugged landscapes for which she is renown, seascapes, portraits, still life and native birds. Her work graces WA’s parliament House, the University of WA, Royal Perth and Geraldton Regional hospitals, Geraldton, Bunbury and Melville city councils, Mullewa Shire Council, and private collections in the USA, UK, Japan, Singapore, and every state of Australia. More of her work is likely to go overseas in future, with several foreign buyers recently showing a keen interest. But this website will ensure all can see West Australia as Ailsa Small sees it, and maybe through her painting they will be as moved by its beauty as she is.

AWARDS

1961,1965,1969 and 1970 – Winner Claude Hotchin Art prize

Winner Geraldton Festival

Winner Bunbury Art Award

COLLECTIONS

Parliament House of Western Australia

University of Western Australia

Royal Perth Hospital

Geraldton City Council

Bunbury City Council

Melville City Council

Mullewa Shire Council

Private collections throughout Australia, Great Britain and America

EXHIBITIONS

Solo Exhibitions

1965 Claude Hotchin Art Gallery

1986 William Curtis Gallery

1989 Bay Gallery of Fine Art, Claremont

1991 Bay Gallery of Fine Art, Claremont

1991 Retrospective Exhibition, Geraldton Regional Art Gallery

2004 Stafford Studio Art Gallery, Claremont

Mixed Exhibitions

1951-1972 Claude Hotchin Art Gallery

1961 The National Heart Foundation Exhibition

1967-1968 Redcliffe Art Exhibition, Queensland

1971 Redcliffe Art Exhibition, Queensland

1974-1976 Rotary Club of Camberwell, Victoria

1979 Western Australia 150th Anniversary Board

1988 “Birdsong” Bay Gallery of Fine Art

1993 Ailsa Small and Mike Vandeleur, Geraldton Regional Art Gallery

2006 “The Four Sisters” Goldsmiths Hall Gallery, Geraldton